Figure 1: Visualization of 30 Music Video mashups taken from YouTube. Mashups were uploaded between 2006 and 2011

I am currently finalizing research on 30 YouTube music video mashups, uploaded between 2006 and 2011. I started this research during the last days of my post-doctoral work at the University of Bergen in May of 2012. I was able to refocus on this project during 2015 thanks to the support of a Faculty Research Grant from The College of Arts and Architecture at The Pennsylvania State University. I thank them for their ongoing support. In what follows I will introduce the principles of this research project.

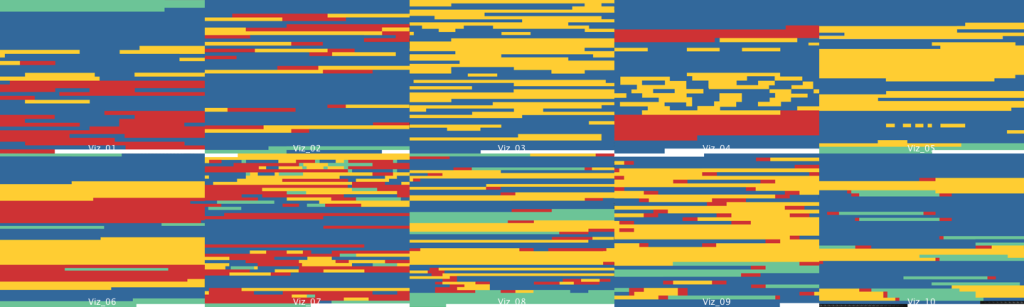

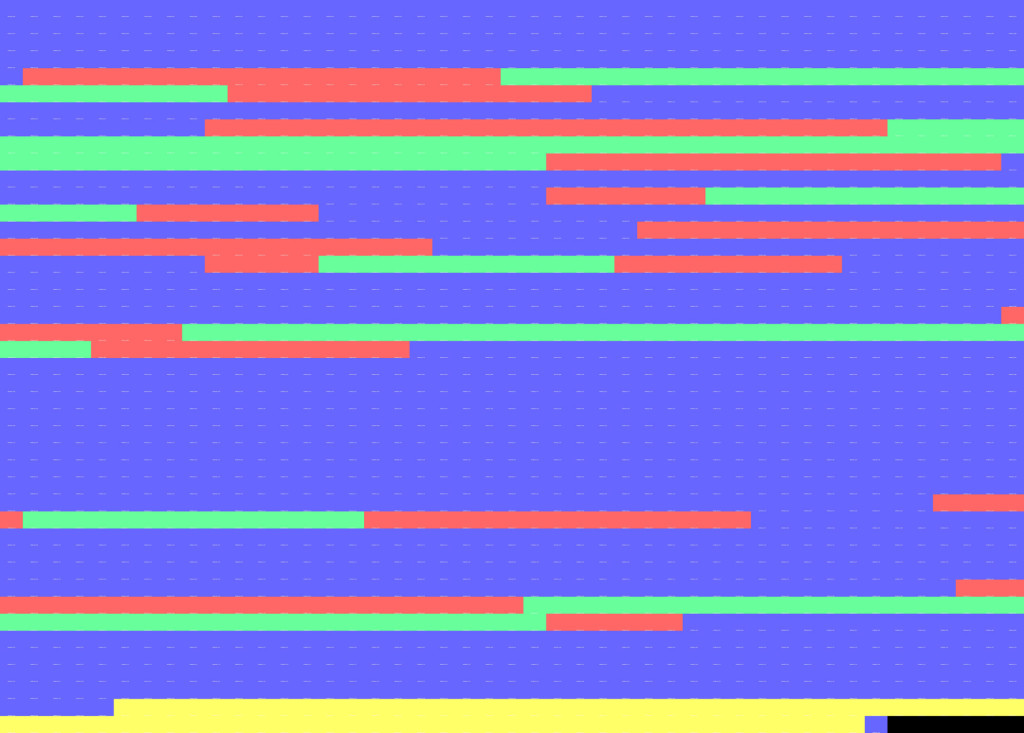

Figure 2: Preliminary Visualization of the first 10 of 30 music video mashups. The list includes from top-left to bottom-right: 1) Danger Mouse Encore (Grey Album, Jay-Z and Beatles), 2) Radiohead vs. Dave Brubeck, 3) 99 Problems with Buddy Holly, 4) Ray of Gob (Madonna vs. Sex Pistols) , 5) The Strokes vs. Christina Aguilera, 6) Eminem Featuring Aerosmith Sing On For The Dream Moment, 7) Blondie Vs. The Doors – Rapture Riders, 8) Boulevard Of Broken Songs – Green Day ; Oasis ft.Travis ; Eminem, 9) Sour Glass (Portishead vs. Blondie vs. Kanye West), 10) Weezer vs. Queen.

Color code: light-green = special effects or titles, blue = main-track/instrumental, yellow= lyrics/complementary track, red = footage of both videos combined.

During my postdoctoral research I worked on three case studies of YouTube video memes. I published my findings in the paper “Modular complexity and remix: the collapse of time and space into search” Based on the editing patterns that I noticed the YouTube video memes shared, it became evident to me that a particular grammar and syntax was at play in the way people edited diverse forms of music video remixes; this grammar also appears to be linked to the way music mashups are produced and function, and for this reason, after I finished my research on the music-video memes, I decided to look further into video-music mashups. I chose 30 of the most popular mashups between 2006 and 2011. Given that remix as a form of cultural production is closely linked to basic music remixes it is worth evaluating how meme patterns move across different genres that combine image and sound as a single form of expression. Music video mashups are good case studies for this reason.

To analyze the patterns of the memes more accurately, I realized that it was not enough to visualize a grid of the video footage as I had done for my previous research. I needed to see how the footage of different videos was edited as one to complement the actual music remix. Therefore, I developed a color-coding system to mark the video edits. I did the first 10 manually, by laying color over the video montage (Figure 2).

This process took too long and was not very accurate, so I developed a batching method in which I evaluate the frames that correspond with the original music videos and assign them a numbered sequence that can then be run to create a montage that matches the original video montage. I share the examples of the first three videos below.

Figure 3: “Danger Mouse Encore (Grey Album, Jay-Z and Beatles)” Grid-montage of music video mashup. Video available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qFd1QvNPKmI

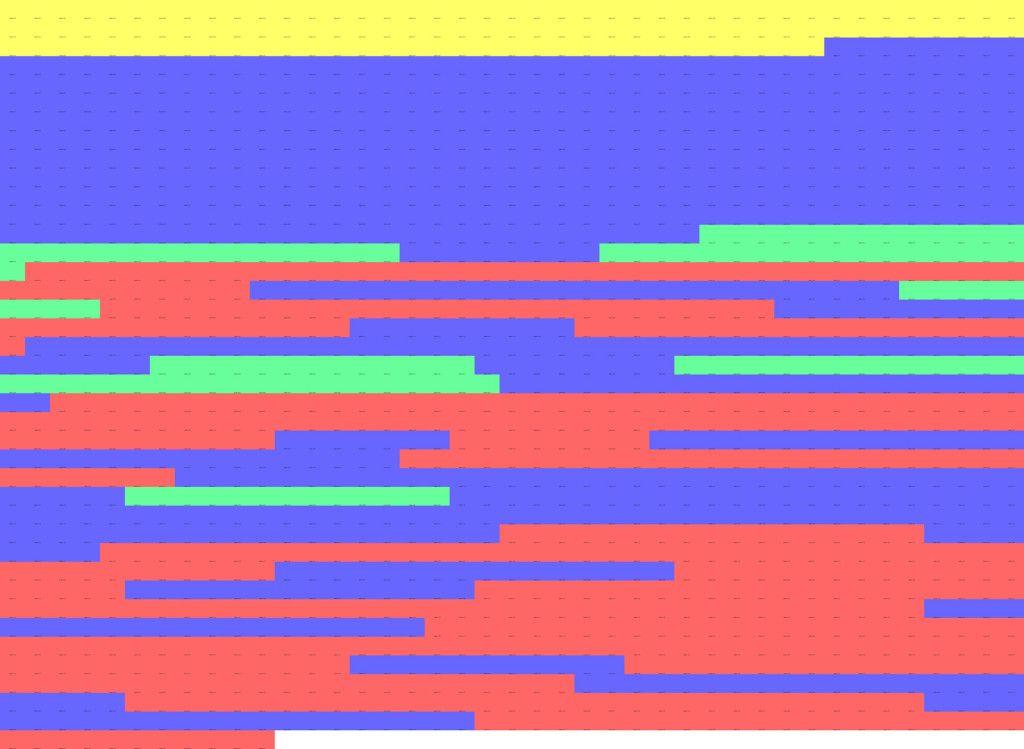

Figure 4: “Danger Mouse Encore (Grey Album, Jay-Z and Beatles)” Video color-coded pattern. Color code: yellow = special effects or titles, blue = instrumental/main-track, green = lyrics/complementary track, red = footage of both videos combined–or hybrid video with special effects.

Figure 5: “Radiohead vs. Dave Brubeck” Grid-montage of music video mashup. This version is no longer available on YouTube, but an alternate remix can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0PQQPUb8Rl0

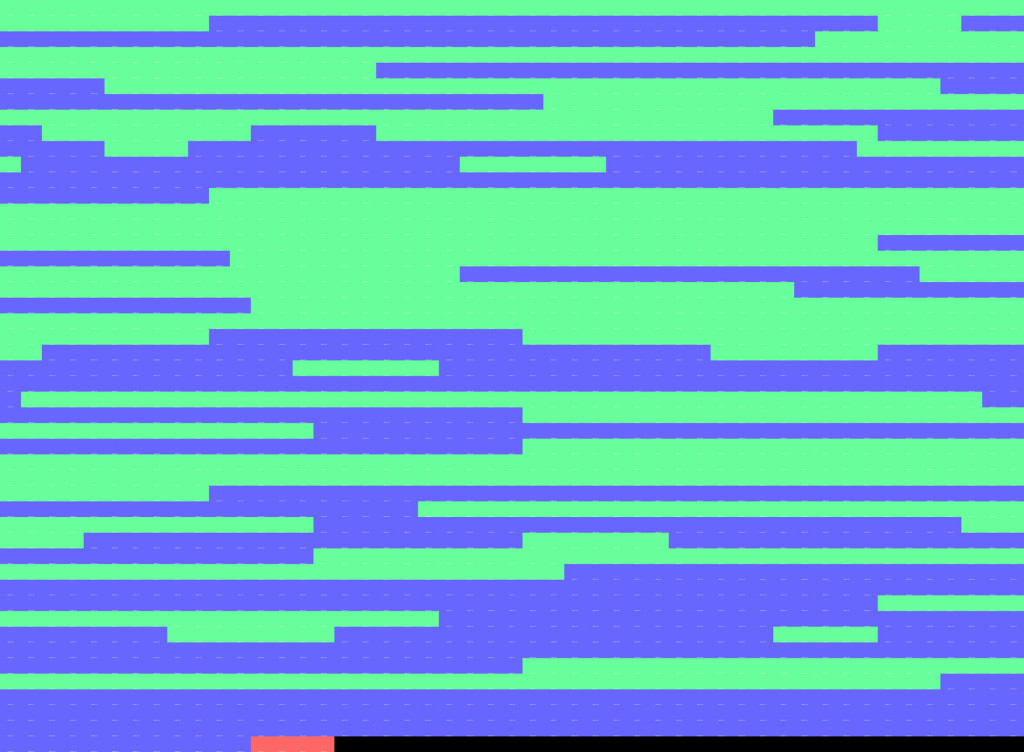

Figure 6: “Radiohead vs. Dave Brubeck” Video color-coded pattern. Color code: yellow = special effects or titles, blue = instrumental/main-track, green = lyrics/complementary track, red = footage of both videos combined–or hybrid video with special effects.

Figure 7: “99 Problems with Buddy Holly” Grid-montage of music video mashup. Video available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4bUAzC9wgkw

Figure 8: “99 Problems with Buddy Holly” Video color-coded pattern. Color code: yellow = special effects or titles, blue = instrumental/main-track, green = lyrics/complementary track, red = footage of both videos combined–or hybrid video with special effects.

Based on these three videos we can see that the approaches vary but nevertheless there are some similarities already evident. For one thing, there is a need to go back and forth between footage in order to reinforce the fact that the video is of a music mashup of two songs. The first two videos show some aspect of the video (red) that supports the aural experience of the sound mix colliding. This is also evident in my preliminary visualization of the first ten videos (figure 2). There is an exception of two videos (mashups 3 and 5), which don’t have any combined or hybrid footage (red), but only juxtapose material of the originating sources. When listening to the actual music remix, it becomes evident that it is because of the way the two songs are mashed that the videos are edited with basic montage. In all of the videos I have analyzed thus far, the image appears to support as best it can the aural experience of the remix. The reasons behind this begs a detailed theoretical examination. It is my aim that my analysis will provide a good sense of how image and sound complement each other in music video mashups. I have looked at more recent mashups on YouTube since 2012, and find that the elements in the 30 videos I am analyzing are still at play. This may mean that certain aesthetic and expressive conventions of communication are already well in place among video and music remixers. In the future, I will be sharing more details of my findings on all 30 videos in a formal paper.