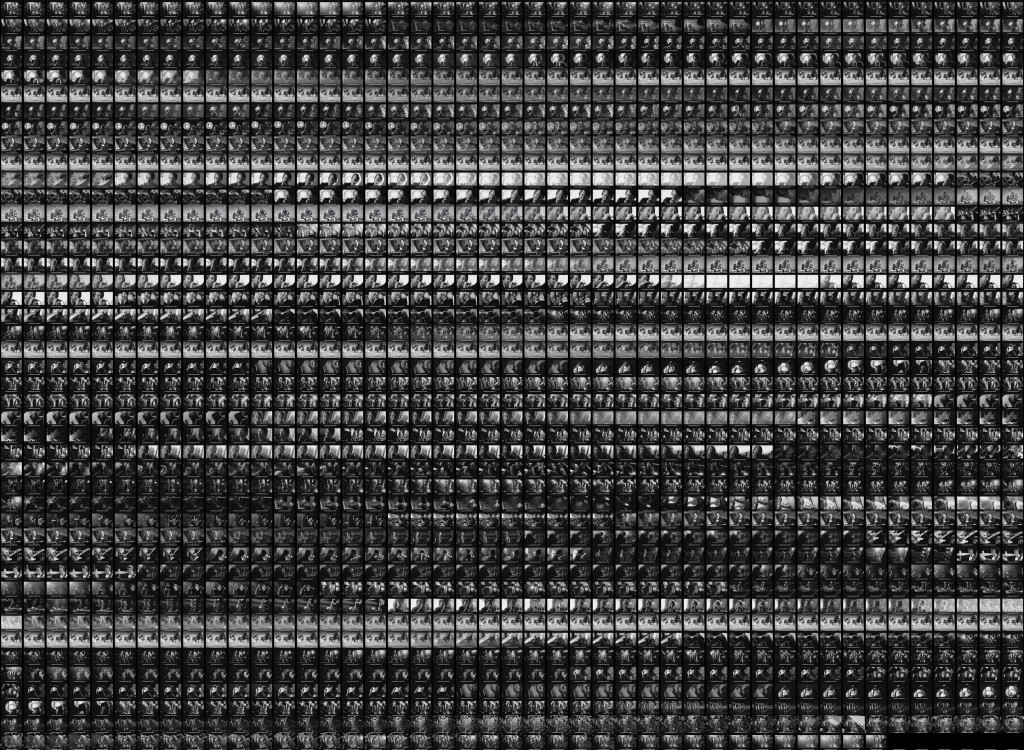

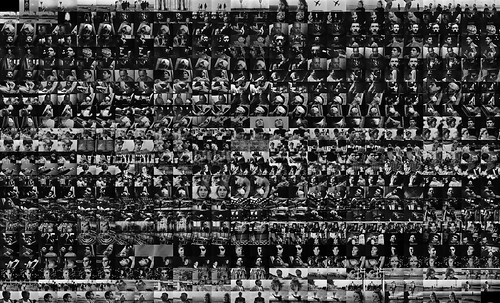

Figure 1: Grid-montage visualization of La Jetée (1962) by Chris Marker A film I have been teaching for basic montage editing with still images is Chris Marker’s La Jetée.

Figure 1: Grid-montage visualization of La Jetée (1962) by Chris Marker A film I have been teaching for basic montage editing with still images is Chris Marker’s La Jetée.

After the film’s screening, during class, we usually discuss the types of shots used, and their timing in relation to sound. One thing that becomes evident when visualizing the film as a grid-montage (figure 1) is that there are a lot of close ups. It is therefore worthwhile to evaluate the pervasiveness of the close-up in Marker’s film in order to understand how it is used to tell the story of a time traveler.

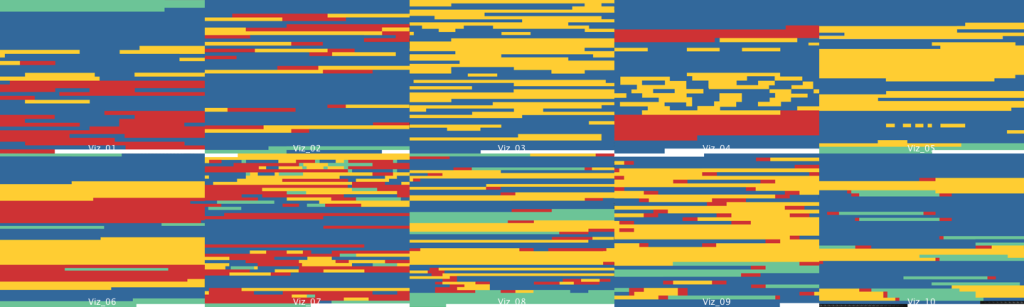

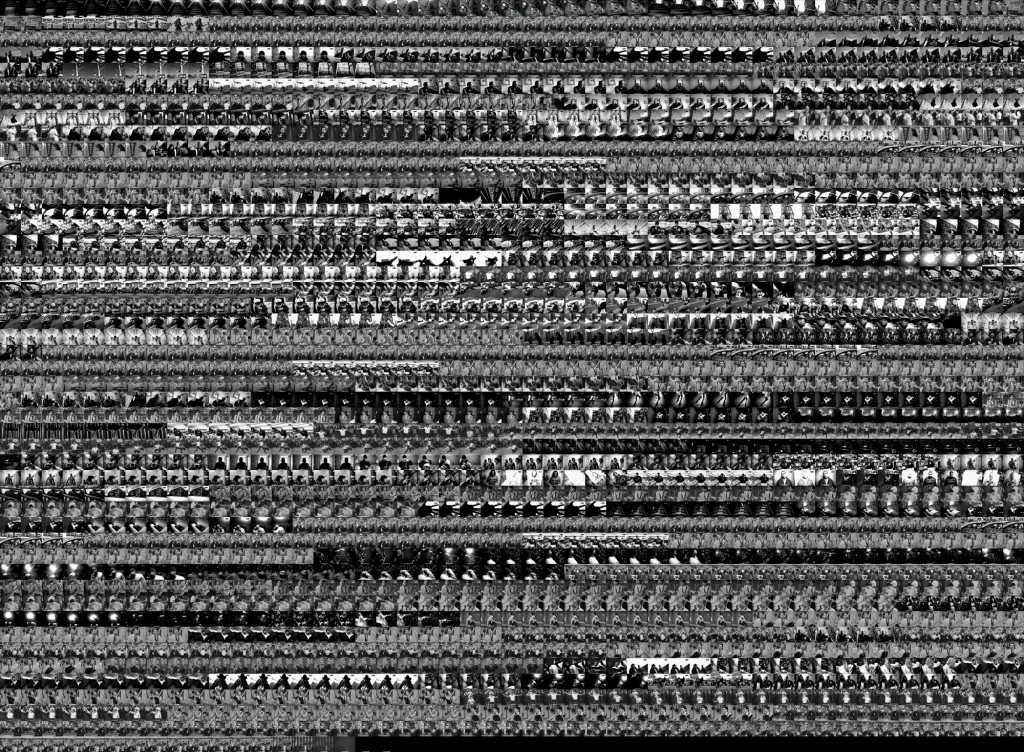

Figure 2: Color coded Grim-montage visualization of La Jetée (1962) by Chris Marker

As we can see from the grid above (figure 2), most of the film is made of close-ups. These shots could be divided into various categories but for this brief analysis, I chose shots that included a single person’s face in a frame. There are other close-ups of hands and text that repeat, which are also included for a general count, along with occasional shots of two persons if they offered a more or less abstract environment. There are about 135 close-ups in the film. And they become predominant once the basic environment in which the story takes place is established. Based on this Marker organizes the film into three sections. The first part set-ups what happened in Paris, and how humans had to go underground to survive. Establishing shots of this major event is combined with shots of an airport, where a mysterious murder is witnessed by a woman.

The basic structure of the film for the first two sections is that of establishing shots and mid-shots moving into close-ups. After this the film goes back and forth between time realities using action shots or close-ups to create psychological tension. There are a few establishing or whide shots during key moments, such as when the hero and the woman visit the museum. But close-ups, action shots and wide shots will not be combined until the end of the film, when we find ourselves in the airport, which, as we learn at this point, is also the beginning of the film. And we come full circle.

Based on this general analysis which could expounded in much greater detail for each section of the film, we find that the close up is effective for Marker because of two reasons.

1) It displaces the environment in which the story takes place and this pushes the viewer to engage with the characters directly as people.

2) On a pragmatic and practical level, it is economical in terms of a budget because little expense goes into the set.

The results of this is tension and drama that is built through affect, meaning that we are pushed to identify with an image in abstract fashion based on empathy and/or sympathy.

The last third of the film may be hard to follow because there are no wide or mid shots during the hero’s final debriefing. The viewer bluntly confronts a series of faces that stare at each other, or sometimes straight ahead–just off camera. There is much more to be said about La Jetée‘s structure, and why it is considered one of the greatest films ever, but one of the reasons why this film is historically important is due to the fact that it makes the most of the close-up, or affect image, to develop a sci-fi psychological thriller that defies film genres to this day.