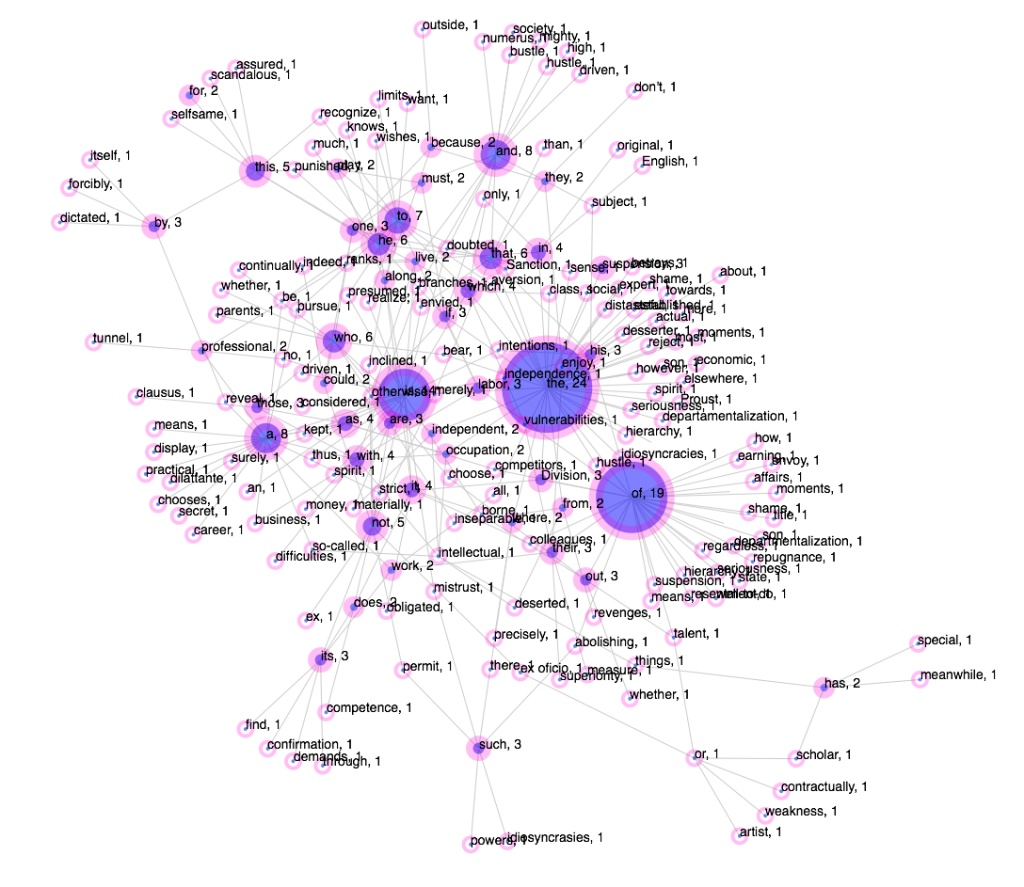

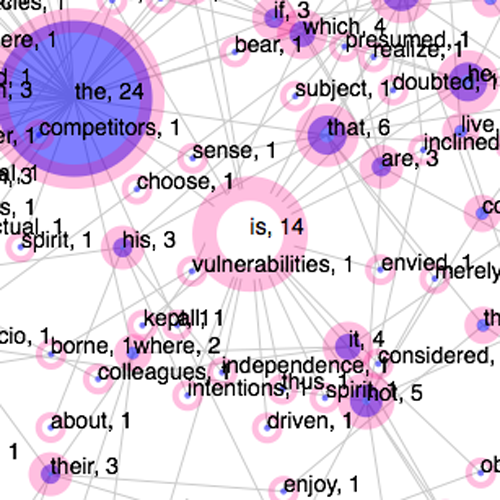

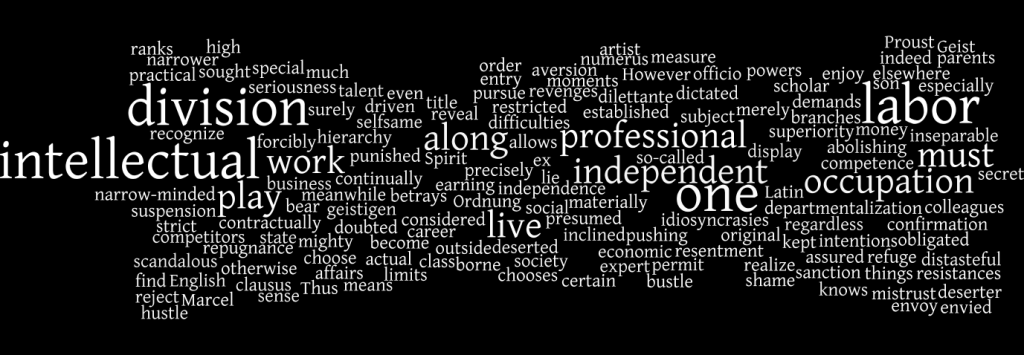

Figure 1: Detail of Minima Moralia Redux Remixes 51 – 55. First set of entries part of the second part of Minima Moralia Redux.

Note: This entry was updated on April 19, 2015 in order to add details on formal aspects of the project.

Minima Moralia Redux, a selective remix of Theodor Adorno’s Minima Moralia, enters a second phase in 2015. This was not foreseen when I began the project back in 2011, because the work is not only a work of art, but also research on data analytics, as well as a critical reflection on networked culture.

The first part of Minima Moralia Redux (entries one to fifty), consisted of updating Theodor Adorno’s aphorisms–that is to remix them as contemporary reflections of the way global society and culture is engaging with emerging technology. When I finished the first section, I realized that the project’s aesthetics were changing. This was for a few reasons. In terms of research, the first section provided more than enough data for me to data-mine Adorno’s approach to writing; therefore, I came to see no need in following this methodology. I plan to make my findings about this aspect public in a formal paper in the future.

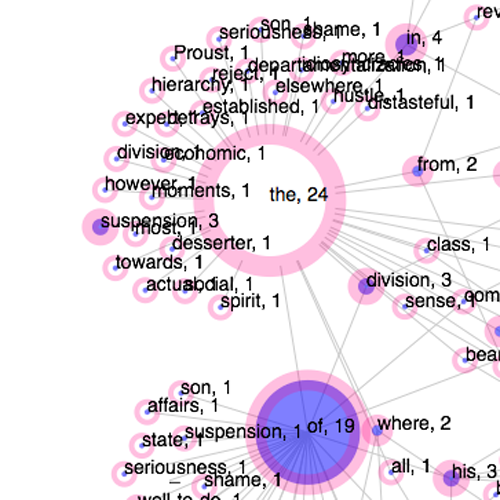

Figure 2: “of the truth comes,” part of a sentence of Minima Moralia’s aphorism 54 that, when clicked, opens a Google search with relevant results.

In terms of art as a form of reflection on the times it is produced, it became evident to me that Adorno’s writing needed to be connected directly with the network on which it functions as a remix; and for this reason, I opted for the current format, which consists of the text as it is available in English at Marxists.org, translated by Dennis Redmond.

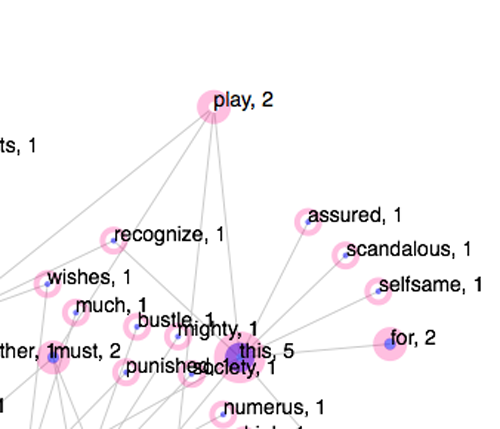

Figure 3: “Truth,” part of a sentence of Minima Moralia’s aphorism 54 that, when clicked, opens a Google search with relevant results.

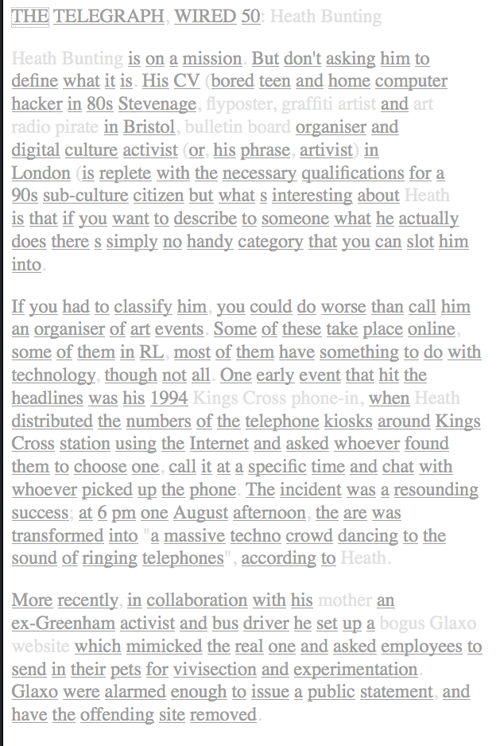

The format for part two of my art and research project consists of linking phrases, parts of phrases, or just single words, devoid of any punctuation, to corresponding Google searches. (Figures 2 and 3) The reader can click on any link and be taken to respective search results, which will change according to Google’s updates on its search engine. The concept of making every word in a text a link is certainly not new. Heath Bunting had already explored this concept with his early net.art piece called readme (Figure 4), in which he took every single word in a review of his own work published in The Telegraph, and linked it to corresponding .com URLs, some which did not exist at the time, but Bunting’s proposition was that one day they likely would.

Figure 4: Heath Bunting, “Readme,” (1998). Online artwork that links all words of a Telegraph review of Bunting’s work to specific .com URLs.

The second phase of Minima Moralia Redux functions more or less in the same way as Bunting’s work, only in this case, the words or phrases are linked to search results as opposed to specific URLs. In this way, Adorno’s second section of his book becomes interconnected with an apparatus (networked communication) that he likely would have been quite critical of. The second part of Minima Moralia Redux, consequently, is an intertextual mashup of Bunting’s early net.art piece and Adorno’s writing.

The above is made possible based on complementary technical and formal implementation of data-visualization. To develop visualizations in support of the new format of links to Google searches, I decided to keep using word-cloud visualizations, at this point Wordle (I used Many Eyes in the past), which provide an emphasis on certain terms for each entry. The number of words vary, and may range from three to as many as sixteen. These words are then used to perform an image search on Google. I then take a screenshot of the top results and place it at the top of the entries. I also input the text for each entry on Voyant in order to see the overall word frequency and their contextual relation (I don’t include my qualitiative analysis of the entries at this point, but it is important for future in-depth evaluations of the project). The text-mining results, along with the word-cloud visualization are placed at the bottom of the page to share the sources used in the development of each blog entry.

Beyond these formal and technical aspects of the project, there is another layer in the second phase of Minima Moralia Redux. It also borrows from Traceblog a previous blog project which I finished in 2013. In Traceblog I made public, ghost logs of my searches online. The logs were fake results produced with a free plug-in for Firefox called Track me not. In Traceblog I wrote nothing, but rather made available material that was produced based on the “disguising” of my online activity. The second part of Minima Moralia Redux is similar in that I don’t produce anything, but rather repurpose pre-existing content, in this case Adorno’s aphorisms, which, when put through a search process, give way to showing how search is connected to content online. This type of writing is more a form of curating the sentences, phrases, and words to provide searches that do not lead directly to Adorno’s book available on Marxists.org, but to the phrases that form Adorno’s argument as they may appear on thousands of websites at divergent times.

This led me to realize an important aspect of sampling in general that I plan to develop further in theoretical essays, but anyone who has followed my argument thus far will find evident in this brief reflection, which is why I think I must elaborate on it at this point.

What the linking of phrases or words for each entry in the second part of Minima Moralia Redux makes evident is how we come to develop what we may consider original content. I realized that if I put an entire sentence into a google search I would have Adorno’s publication at the top of the search, which meant that Google was able to recognize the string of terms as a direct “sample” from Adorno’s writing. I wanted to get diverse results that did not lead to Adorno directly, so I decided to adjust the search to a string of words that would provide a result that would not bring Adorno’s text within the first page of results. This at times is not possible, but what becomes evident in this process is that we develop our own work from things that are pre-existing. A single word search is likely to provide the most diverse result on Google, but the more specific the string of words, the more likely one is to reach a specific “sample” that may be deemed the original work of a particular person.

In effect, this second phase of Minima Moralia Redux exposes that what we tend to recognize as someone’s creation in any media is really a specific combination of elements that are mashed together by producers according to what they want to communicate, or express. In effect, even when we speak, we are borrowing from a set of samples (words) archived in a database we carry, called our “memory.” Such combinations are seen as “property” when they are placed in a format that is more static–a product. With the speed of network communication, however, the static state of things is coming to an end, and the ever-changing state of forms produced (viral memes are an early example of this) will become valued more than a single instance of production.

Nothing is original, just unique.