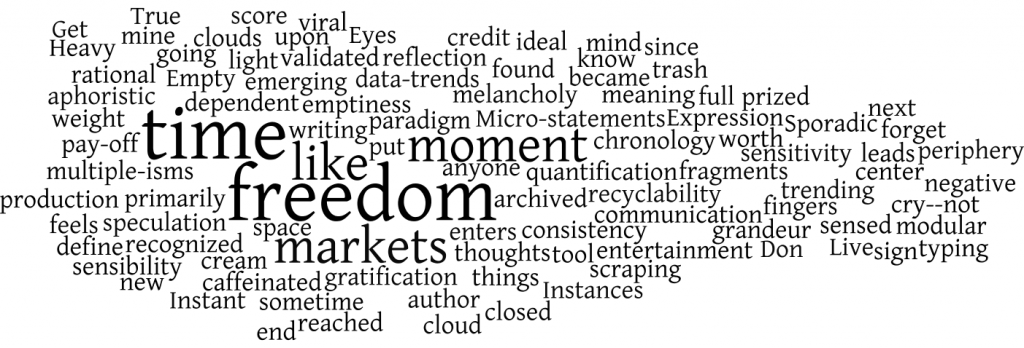

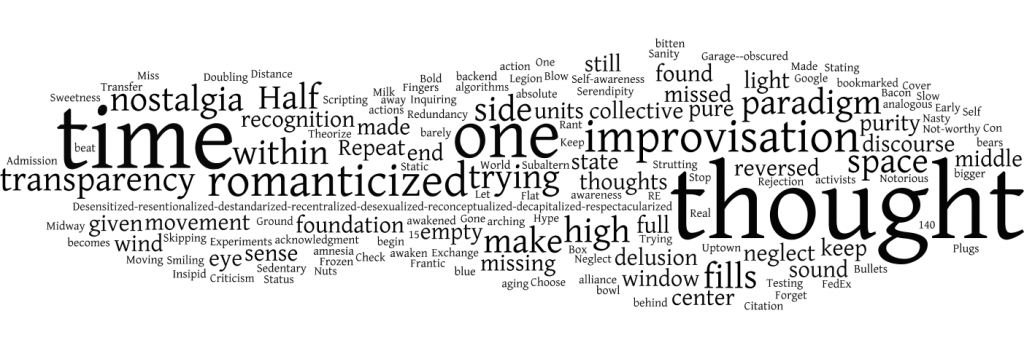

Figure 1: The five most repeated words from 2010-2013.

Poemita began in 2010. It means little poem in Spanish. The basic premise was to experiment with tweets as new forms of writing. I eventually decided to use it as a resource (think of it as data mulch) for various projects. Some of the tweets are being repurposed as short narratives, which I have not released. Poemita was actually preceded by writing I developed for my video [Re]Cuts, a project influenced by William Burroughs’s cut-up method. I am in the process of producing a second video that uses actual tweets from Poemita.

I worked on Poemita on and off, sometimes not posting for months at a time. In fact, I don’t have a single post for the year 2011. But during the month of August 2014, I realized that Poemita has been a project that is closely related to my ongoing remix of Theodor Adorno’s work in Minima Moralia Redux. It could be thought of as a negative version of that project (I am using the term “negative” here in dialectical terms). To allude to this relation, I inverted the color scheme for the word cloud visualizations of Poemita to be the opposite of Minima Moralia Redux’s. Poemita takes the concept of the aphorism as Adorno practiced it and tries to make the most of each tweet. Most of the postings are well under 140 characters, and they all try to reflect critically on different aspects of life and culture. I try to do this creatively, and write content that may appear difficult to understand, but ultimately may not even make sense; the aim is to create the possibility for the reader to see things that would not be possible otherwise. In short it is an experiment in creative writing, and this is why the project was titled Poemita.

I may not be able to post consistently, but I will certainly be posting tweets more regularly then before. And I will eventually be repurposing the tweets in different ways to explore how context and presentation along with selectivity are ultimately major elements in the creative act. This will become clear as I release the tweets in different formats in the future. This, in essence, is a way of remixing data.

To reflect on where this project is going, I decided to analyze it as I would other texts to understand how it is constructed, and to evaluate the type of patterns that may be at play in my online writing. What follows, then, is a set of studies of the tweets for the years 2010, 2012 and 2013. I will be releasing analysis of 2014 later, after the year is over.

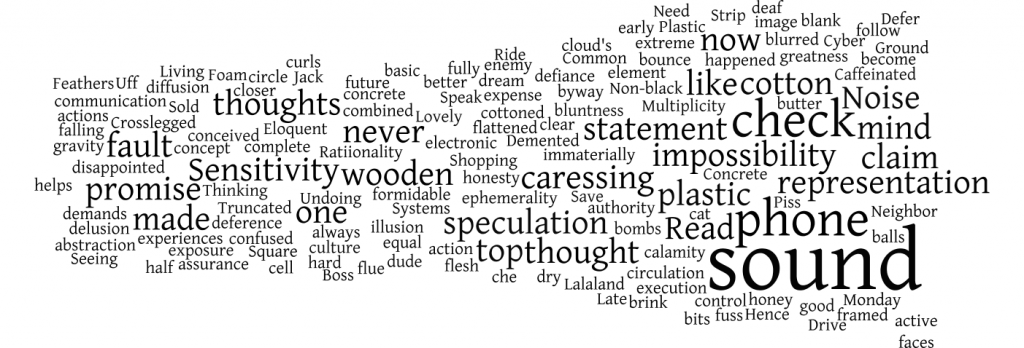

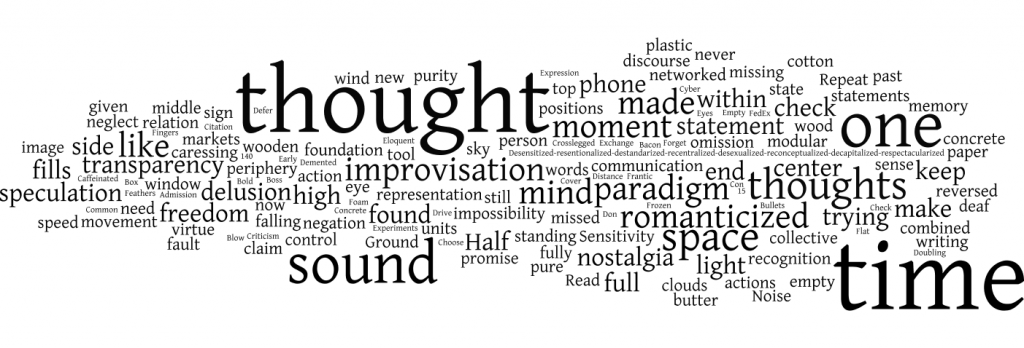

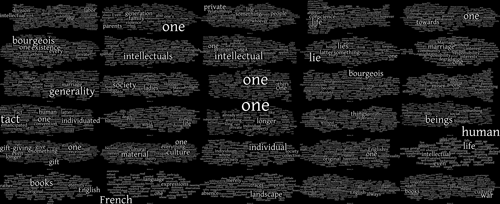

First, it is worth looking at word clouds for the three years:

Figure 2: Word cloud of tweets for 2010

Figure 2: Word cloud of tweets for 2010

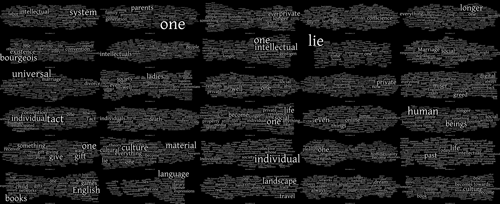

Figure 3: Word cloud for tweets of 2012

Figure 4: Word cloud for tweets of 2013

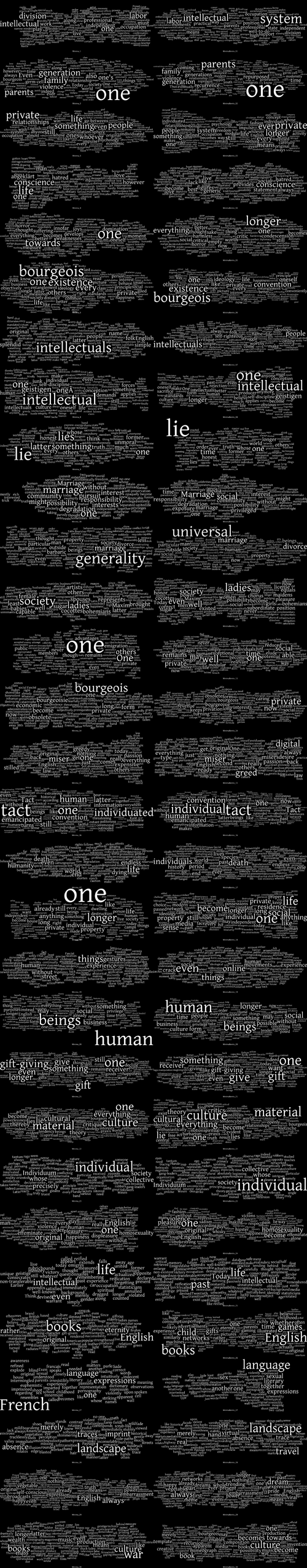

Figure 5: Word cloud of tweets from 2010-2013.

We can note the top four or five words for each cloud for the respective years of 2010, 2012, and 2013 and consider how they eventually become part of the larger cloud for all of the years of 2010-2013. The number of occurrences could be accounted for yearly, but for the current purpose of this analysis, it should be sufficient to evaluate the number of words in the largest cloud for all three years (figure 5).

In the cloud above (figure 5), then, there are a total of a 1,712 words and 863 unique words. The most used words besides articles and prepositions appear much larger. These words appear the following number of times in the actual body of the text:

Time: 12

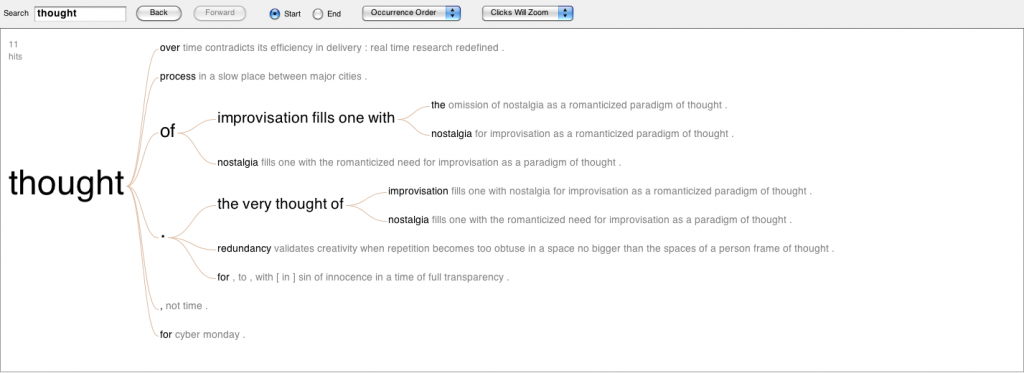

Thought: 11

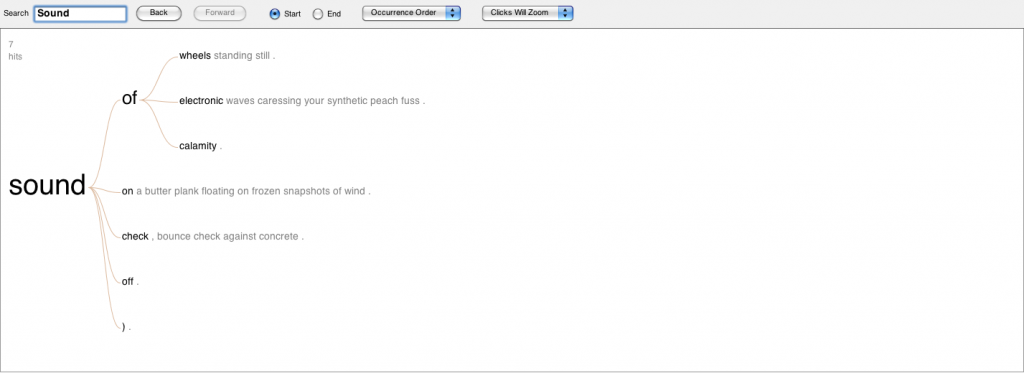

Sound: 7

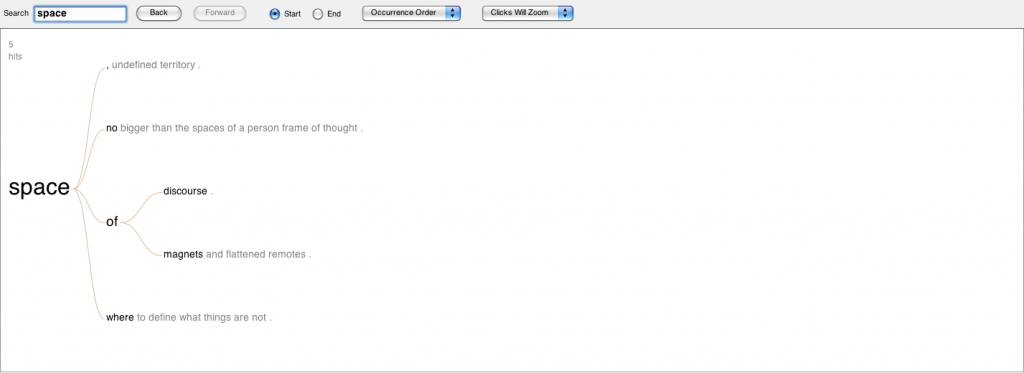

Space: 5

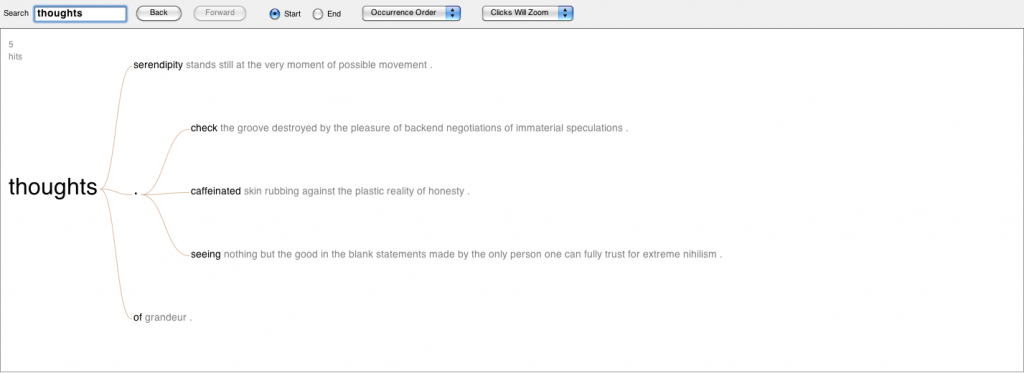

Thoughts: 5

The word trend chart at the top of this page (figure 1) shows how these words relate to each other in terms of writing sequence. If you were to choose a particular node, you would be taken to the actual text and shown how the word appears in its context. The tool I used to this word analysis is Voyant. Seeing the words in a diagram provides a visual idea of how they relate to each other within the actual writing.

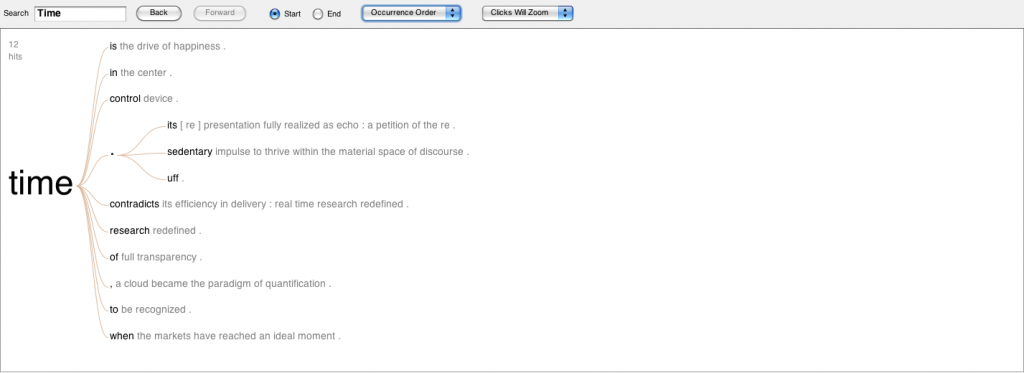

This gives a sense of repetition, and may even allude to certain interests in terms of content and ideas within the corpus of the text, but it does not provide a clear sense of how the words actually function, or under what context they recur. For this, the way the words are used in actual sentences can be mapped. In the following word trees, the top five words (in order of times repeated), Time, Thought, Sound, Space, and Thoughts are linked to all the phrases that follow them:

Figure 6: The word “time” linked to the phrases that come after it. Click on the image to view a larger file.

Figure 7: The word “thought” linked to the phrases that come after it. Click on the image to view a larger file.

Figure 8: The word “sound” linked to the phrases that come after it. Click on the image to view a larger file.

Figure 8: The word “space” linked to the phrases that come after it. Click on the image to view a larger file.

Figure 9: The word “thoughts” linked to the phrases that come after it. Click on the image to view a larger file.

The word trees above show how each of the words are implemented to create particular statements. At this point, it is possible to make certain assessments. Let’s take the word “thoughts” (figure 9). We can see that three out of five times it comes at the end of the sentences. We can also note that the exception to this is a reflective statement: “thoughts of grandeur.” Let’s take a look at the word “thought” (figure 7) and we can notice that it is part of a much more complex set of phrases. Two times, the word is part of the branching recurrences “Improvisation fills one with…” and “the very thought of…” But notice that in the last one thought is also followed by a period.

Finally, we can consider the words that come before these words. Let’s take the word “thought” for a brief example. For this we can use voyant:

At this point we can get a full sense of how the word recurs and how it functions each time it appears. This approach puts me in the position to evaluate what similarities and differences their implementation may share in order to evaluate particular tendencies I may have in my writing.

We could go on and examine the other top words in the same way, but this is enough to make my point. It becomes evident that how the word “thought” and its plural “thoughts” are used has much variation in the creative approach in terms of twitting. At least, I, as the actual writer, become aware of the way that I tend to relate to the singular and plural instantiation. This in the end is a reflective exercise that enables me to be critically engaged in understanding my own tendencies as a writer. I plan to use this analytic approach to further the possibilities of writing tweets that can offer a lot more content just under 140 characters.

One of the issues that I assess in all this is the role of repetition. One may think that repetitive occurrences are bad for creativity, but in practice, it is through repetition that we come to improve our craft and technique in any medium. In terms of how words are used or repeated, with analytical exercises like this one, a writer can come to understand how certain words recur and under what context, to then decide if to implement them differently or omit them altogether in future writing.

I certainly was not thinking that I would use these words the most when I began writing in 2010. They appear to recur and I’m not sure why, but the point is that now I can use this awareness to improve my own creative process.

This analysis can get very detailed, obviously, but this should be enough at this point. This is just a brief sample of how I am data-mining my own writing to also develop other projects by remixing the content. I will also be mining twitter postings to evaluate how what I learn in this focused project may or may not appear to be at play in the way online communities communicate.